So you’ve finally finished writing your novel and have edited the heck out of it. You’re exhausted, and probably over caffeinated and sleep deprived, but the pains of your efforts have been well worth it.

So you’ve finally finished writing your novel and have edited the heck out of it. You’re exhausted, and probably over caffeinated and sleep deprived, but the pains of your efforts have been well worth it.

You cradle your newborn manuscript you’ve brought into this world. You’ve now reached the moment of truth–you’re ready to submit to agents.

It’s a scary thing sending your defenseless little manuscript out into the world. Agents and editors can be vicious, and the last thing you want is for your baby to get rejected. So before you start querying, it’s important you take the time to properly format your manuscript to give it it’s best chance of getting adopted by a publisher.

This is not a step you do not want to skip over! I know you’re itching to submit to agents, but wouldn’t it be a shame for all of your hard work to be for nothing because you were too lazy to do a little formatting?

“But do agents even really care about formatting? Aren’t they just interested in my story?” you ask.

Oh yes. Trust me, agents care. And they take notice of sloppy formatting. It will earn your manuscript a one-way ticket to the slush pile. Why?

First, poor formatting can make your story difficult to read. If an agent has a whole stack of manuscripts on their desk to sort through, they’re not going to take the time to struggle through yours. You don’t want to annoy the person who could get your story published!

Second, your formatting reveals who you are as a writer. If your manuscript is properly formatted, the agent will think “Oh, this writer knows what they’re doing. They’ve done their research and have taken the time to present themselves as a professional.”

But if your manuscript is a hot mess, it sends up a red flag and signals to agents that you’re an amateur and/or lazy. “Man,” they’ll think, “If the formatting is this big of a mess I don’t even want to know what the writing looks like. It’s probably a train wreck.”

Plus, it’s just rude to send an agent a sloppy manuscript! Don’t waste their time.

If the idea of formatting freaks you out, relax. It’s not as complicated as it sounds–and I’m here to help you out! I got your back. 😉 I’m going to show you how to format your manuscript professionally according to industry standards so you’ll get on the good side of agents. Ready? Let’s do this!

Proper Manuscript Formatting

Step 1: Always, always check the agent’s publishing guidelines first! Mostly they all tend to be pretty much the same, but sometimes they vary. So do your research and adjust your manuscript accordingly.

Step 2: Set your font to black, size 12 Times New Roman font. (Do NOT try to be artistic and make your manuscript stand out by using weird fonts).

Step 3: Set your margins to 1 inch on all sides.

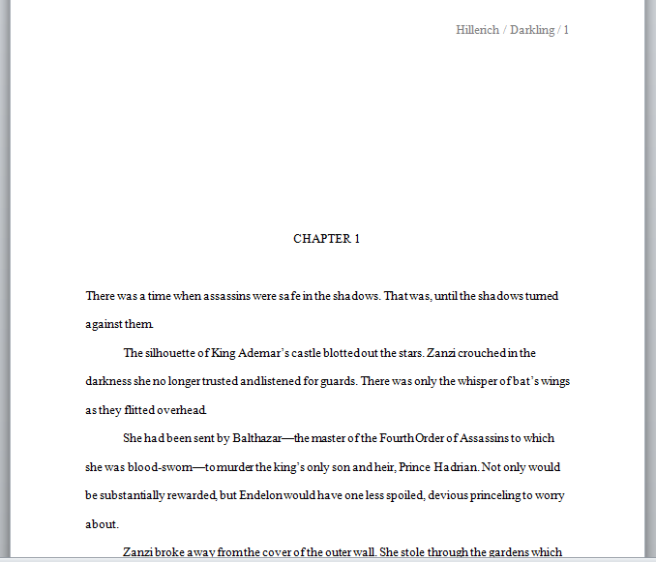

Step 4: Create a title page. Type your name, address, phone number, and email in the upper left-hand corner of the first page, single spaced. Then, place the word count of your story under your email or at the top of the page on the right (round off the word count to the nearest thousand or five hundred). Optional: include your genre or sub-genre above or below the word count.

Next, about halfway down the page, type your story’s title and center it. The title can be capitalized normally or in all caps. Skip a line, type ‘by,’ skip another line, and type your name.

Step 5: On a new page, begin your story. You will start each chapter on a new page 1/3 of the way down (about 6 double-spaced lines), and center the chapter’s title (the title can be capitalized normally or in all caps). Then, skip two lines before starting the body of the chapter. The first paragraph of your chapters or new scenes can either be indented or left flush.

Step 6: Create a header on each page excluding the title page. It should include your last name, the title of your story (or keywords if it’s too long), and the page number. Separate your name, title, and page number with a / and align the header to the right. (Also, make sure your chapter lengths are reasonable. 12-17 double-spaced pages is a good range).

Step 7: Double space your entire manuscript.

Step 8: Make sure all of your paragraphs have a 1/2 inch indent. This is equal to 5 spaces, or make things easy on yourself and use the tab key 😉

Step 9: To indicate a scene break, insert a # between paragraphs and center it. Asterisks *** are also acceptable.

Step 10: To emphasize words, use italics. Don’t underline or bold your words.

Step 11: At the end of your manuscript, insert a # sign or type “The End” and center it. This lets the agent know there aren’t any missing pages.

Step 12: If sending your manuscript through snail mail, don’t staple or bind your pages in any way.

“Um, okay, great but what the heck does this all look like?” you wonder.

Well, allow me to show you.

The title page:

The manuscript pages:

See, that wasn’t so bad, was it?

Now, if you look around online and see variations of the format above, don’t panic or get confused!

There can be slight variations, though nothing real drastic. (For example, some recommend Courier font, but others say it’s outdated. Really, either Courier or Times New Roman is acceptable). This format isn’t the one and only way to do it. I think that’s why writers get confused and stress out over formatting.

Just remember to always check the agent’s guidelines first. And as long as you are presenting your manuscript in a professional format like the one I’ve shown you above, you’ll be fine. Don’t sweat small variations you might see online.

You’re now ready to send out your beautiful baby manuscript! Check out my list of 100 YA agents to get you started.

Still confused? Have questions? Need help? Leave me your comments below!

Sympathetic

Sympathetic